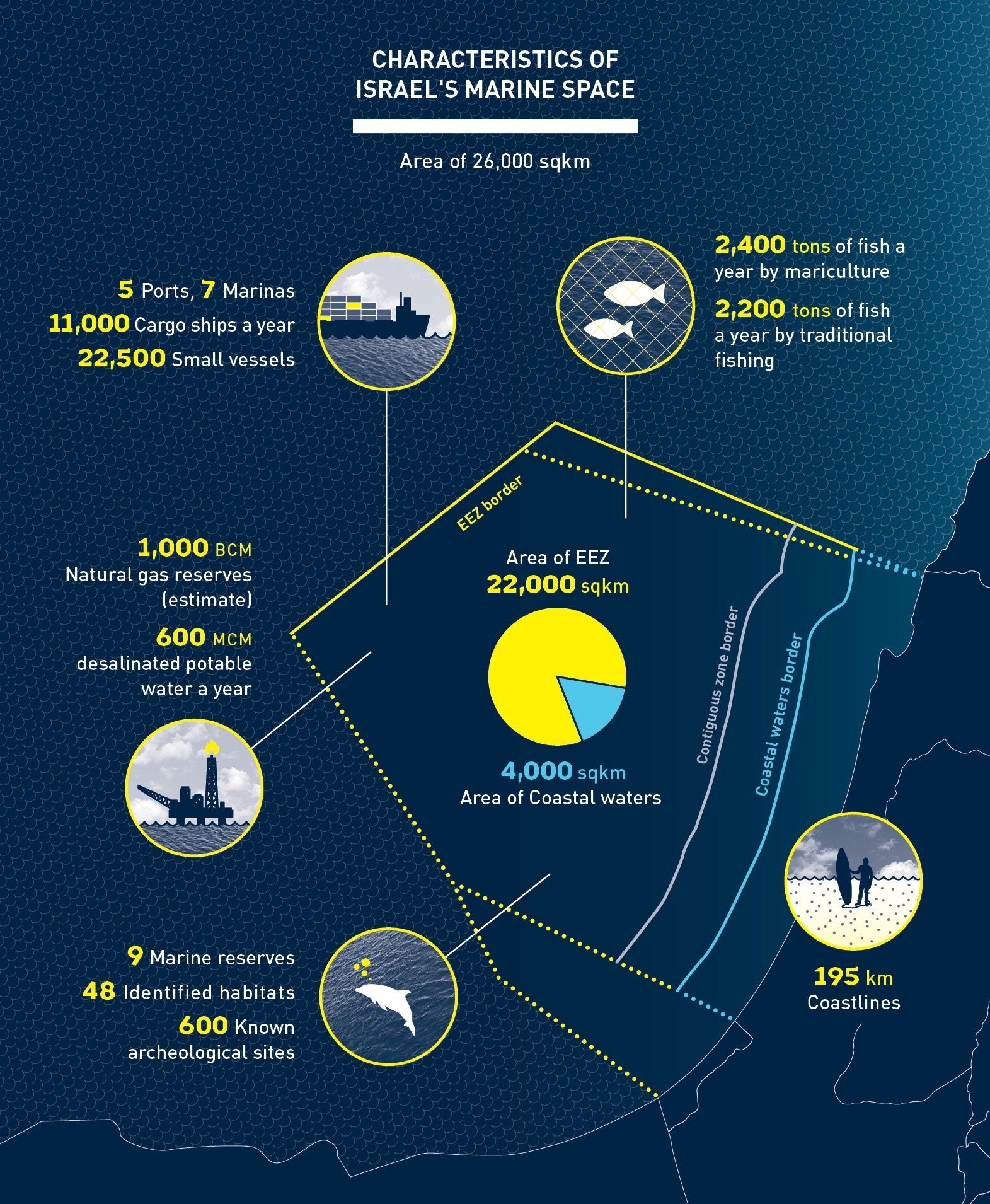

Underlying the initiative to draw up a plan is the understanding that Israel’s marine space is a vast resource, over 26,000 km² in size, larger than the State’s land area. There are three different zones within this area:

- Coastal waters (territorial/sovereign waters) – up to 12 nautical miles westward from the shoreline, with a total area of over 4,000 km². The State has full sovereignty in this area, but foreign vessels have the right of “innocent passage”;

- The Contiguous Zone – a strip that extends a further 12 nautical miles beyond the coastal waters (in other words, between 12 and 24 nautical miles from the shore line), and constituting part of the Exclusive Economic Zone. The State does not have full sovereignty in this zone, but it may operate limited enforcement authority in order to prevent infringement of the law with regard to customs, immigration, sanitation and archaeology;

- The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) – extending beyond the coastal waters to 110 nautical miles (NM) in the south of the country, and 70 NM in the north, to the mid-line between Cyprus and Israel, as agreed between them. The borders of the economic waters in the north and south have been marked as is customary in this matter between countries, but without any consent or agreement with Lebanon or the Palestinian Authority or Egypt. In the EEZ, the country does not have full sovereignty and only enjoys exclusive economic rights: the right to explore, utilize and manage the living and mineral resources on and under the seabed, and in the waters above it; the right to utilize waves, currents and wind for the production of energy; associated authorities to realize these rights, such as building facilities and artificial islands; judicial rights in the area of the facilities, and the authority to determine a safety zone around them. The State also has supervisory and enforcement authorities to exercise its rights to the living resources, and the authority to conduct scientific research and to protect the marine environment. With these rights, the State has an obligation to preserve the marine environment and the living resources. Foreign countries have defined rights in the economic waters, including the right to sail, fly, and lay submarine cables and pipes. Israel has not yet officially declared its Exclusive Economic Zone (as required by the UN Convention on the Law of Sea, UNCLOS).

There is considerable potential in this area for developing and providing a variety of services to Israel’s society and its economy, but also a serious threat to the delicate natural/ecological balance of the marine environment. If realized, this threat could harm the sensitive marine and coastal ecosystems and the services they provide. In the absence of a comprehensive plan for the marine space and effective tools for implementing it, realizing these threats could cause irreversible damage.

National attention to the opportunities and threats in the marine space has increased considerably in recent years, mainly because of the discovery of large gas reservoirs. Attention has also increased due to the understanding that initiatives in and around the area will continue to expand, and that it is also necessary to take into account global changes such as climate change, and geological and political developments in the eastern Mediterranean. This attention has not yet coalesced into a clear spatial policy and effective regulatory tools for planning and managing the space. Therefore, many opportunities are likely to be missed or delayed, while threats become realities.

With similar challenges, many of the world’s developed countries have created in recent years mechanisms for planning and managing the marine space and its resources based scientific knowledge. These mechanisms call for balanced and careful development, preserving the resilience and health of the marine environment while protecting the sea’s resources for the coming generations. Examples include marine spatial planning (MSP) plans – which have developed considerably in recent years, mainly in North America, Europe, and Australia, and the ecosystem based management (EBM) approach, which emphasizes the needs and objectives of the different stakeholders, and creates a synergetic balance between them while preserving a strong, healthy and productive ecosystem. Applying and adapting of the knowledge and methodologies developed around the world to Israel’s marine space is essential.

In recent decades the Israeli sea has become an area of multiple uses and activities, as well as conflicts. Pressures caused by infrastructure and urban and rural development along the coast. The use of the sea itself has multiplied considerably with the discovery of natural gas. The sea is a rich and still to be discovered source of energy, enabling the State of Israel to come closer to energy independence, the development of engineering and technical knowledge, and the creation of supporting industries. At the same time, there is a constant increase in the magnitude of maritime trade. Israel’s sea is its gateway and bridge to the rest of the world. Almost all import, export, and communication, vital to its existence and its continued prosperity and well-being are dependent on the marine space. These require port infrastructures, shipping corridors and maritime routes, control, monitoring and security systems, and an ever more sophisticated network of cables connecting Israel to the rest of the world. Furthermore, for Israel as an “island state” (without peacetime relations with its neighbors), the sea is also a security front and important strategic depth. The greater the opportunities in the marine space, the greater are the threats.

The considerable pressures on Israel’s densely populated land (especially its coastal strip), the doubling of its population within a few decades, its economic activities, and its social needs demand continued examination of the sea as a reserve area for land based development. Various studies show different levels of feasibility of development at sea for the purpose of establishing infrastructure facilities that have a connection to the sea, or those that take up valuable coastal areas, or create wide scale restrictions on dense land areas. The possibility of utilizing the marine space for urban development still appears distant, and it is doubtful whether it is in line with national priorities. Nevertheless, it requires continued research, and creative work, and should not be taken off the planning and technological agendas, or out of the framework of the marine vision for the farther future.

The marine space also contains unique geological and biological features, and rare heritage values. The eastern Mediterranean can be observed and actually used as natural laboratory in which a large part of the world’s marine geological phenomena occur, including significant tectonic activity. There is great biodiversity, some of it unique, which is threatened by many invasive species as well as by increased human activity. The Israeli marine space is also the cradle of early civilizations, coastal and maritime, rich and continuous from the Neolithic period until our times, and offers a fertile bed for research, study, education, and tourism and leisure activities. The Israeli sea is an oligotrophic sea (very poor in nutrients), with very limited fishing resources. Poor management of fishing and actual overfishing has contributed to the depletion of fish, and caused serious harm to essential environmental resources. The Ministry of Agriculture proposes developing controlled mariculture that will develop food from the sea in an economically and environmentally sustainable way.

Despite the considerable development in mapping, data collecting and research in recent decades, knowledge about the Israeli marine space in the Mediterranean, and in particular the deep sea that constitutes the greater part, is still very limited. Furthermore, there is a worrying absence of a national policy to promote marine research and data collecting, to provide sufficient funds for its development and make it accessible. In addition to all of the above, despite the dependence on the marine space and its accelerated use, and despite the awareness of its potential and its environmental and social vulnerability, this area still has fractured administration and limited governance. The marine space is still severely lacking in appropriate legislative tools, effective enforcement mechanisms, and the necessary spatial planning. All these are detailed at length in the Israel Marine Plan Stage 1 report are the foundation for defining the plan’s objectives and for formulating policy measures for realizing them.